Factors Influencing Dietary Diversity and Nutritional Status among Adolescent Pregnant Women in South-Eastern Tanzania: a Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Adolescent pregnancy has become a global health concern in recent years, with maintaining dietary diversity being essential to ensure the health of both the mother and fetus. This study aimed to understand the dietary diversity and nutritional status among pregnant adolescents attending antenatal clinic and identify the factors influencing these outcomes. A hospital-based cross-sectional study was done at St Francis Regional Referral Hospital in Ifakara, Tanzania. A total of 131 adolescent pregnant women consented to participate. Data was obtained using a questionnaire and 24-hour dietary recall. The study revealed that 93.1% (n=122) of adolescent pregnant women met the minimum dietary diversity score based on a 24-hour recall period. Similar proportions were observed for the age group but vary significantly with the number of children born (p< 0.001), marital status (p = 0.032) and education level (p< 0.001). Additionally, 93.9% (n=123) of adolescent pregnant women had a normal Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) and 6.1% (n=8) were undernourished. Similar proportions were observed across age, number of children born, marital status, education status, and occupation. Most adolescent pregnant women in this study achieved adequate dietary diversity. However, socio-demographic factors such as age, marital status, and education, as well as challenges like illness and loss of appetite, influenced their dietary diversity and overall nutritional status. Future research should adopt a community-based longitudinal approach to better understand these factors and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dietary patterns of adolescent pregnant women.

Keywords

Dietary diversity, Nutrition status, Adolescent pregnant, Antenatal care

1 Introduction

Adolescent pregnancy has become a global health concern in recent years. Globally, approx. 16 million adolescent girls aged 15-19 and 2 million girls under 15 give birth each year, with more than 90% of these births occurring in developing countries 1. In Africa, the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy is reported to be 18.8% in the Sub-Saharan region and 21.5% in East Africa 2. According to the Tanzania Demographic Health Survey (2022), the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy in Tanzania is 22%, with higher rates in rural areas (25%) compared to urban areas (16%). Health outcomes as malnutrition, low birth weight and anaemia among others are nutritional-related risks to pregnant adolescents due to dual nutrient demand in their bodies and low adherence to healthy dietary practices 3, 4.

Malnutrition, low birth weight, and anaemia are significant risks associated with adolescent pregnancy due to the increased physiological demands on young mothers 1, 5. These risks are exacerbated by peer pressure, eating habits, inadequate nutrition education, and socioeconomic challenges, further complicating the nutritional status of pregnant adolescents 6, 7. The increased nutritional demands during pregnancy make dietary diversity essential, as there is a direct link between maternal nutrition and fetal development 8.

Dietary diversity refers to the number of different foods or food groups consumed over a given reference period 9. The food groups include carbohydrates (energy-giving foods), proteins (body-building foods), vitamins (supporting metabolic functions and immune health), fats and oils (providing insulation and transportation of nutrients), and minerals (essential for functions) 10, 11. One food item may contain one or more of the food types differing in proportions hence diversity is encouraged to ensure that nutrient demand is sufficiently met by an individual 9. Concerning pregnant adolescents, it is crucial to maintain a diverse diet, as they need to support not only the growing fetus but also their body development 4. Adolescent pregnant women who consume a wide variety of food groups, such as fruits, vegetables, grains, proteins, and dairy products, get vital nutrients like iron, calcium, folic acid, and protein. These nutrients are important in preventing complications like anaemia, preterm birth, and low birth weight 12, 4. However, a study done in Ethiopia stated that inadequate dietary diversity may lead to micronutrient deficiencies such as anaemia, which affects both the mother and growing foetus, but can also result in preterm delivery, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction and abortion 13, 14. In considering the significance of nutrition to these women, interventions have been in play such as nutrition counselling and education to ensure adherence to a healthy diet 10.

Although interventions such as nutrition education and counselling are included in antenatal clinic services, these are often not tailored to meet the specific needs of age groups, specifically pregnant adolescents 4, 15. This gap makes it challenging for them to achieve the necessary dietary diversity while managing the demands of both motherhood and adolescence. Consequently, poor dietary patterns in these young mothers can lead to malnutrition and health complications for both the mother and the newborn 13.

This study aimed to understand the dietary diversity, nutritional status, and factors influencing them among pregnant adolescents attending antenatal clinics by assessing i) dietary diversity, ii) nutritional status of pregnant adolescent girls, and iii) investigating socio-demographics, socio-economic and cultural factors influencing dietary diversity and the nutrition status of pregnant adolescent girls. The findings intend to inform the design of culturally appropriate and context-specific interventions to address the unique needs of pregnant adolescents. We discuss our results in the context of identifying key factors affecting dietary diversity and nutritional status among pregnant adolescents, to develop culturally appropriate and context-specific interventions to support their unique health needs during antenatal care.

2 Methodology

This study was carried out at St Francis Regional Referral Hospital located at Ifakara within Kilombero district, Morogoro region of Tanzania. It is located at 36° 40' 46.44" S and -8° 8' 42.47" E in South-eastern Tanzania. Saint Francis Regional Referral Hospital (SFRRH) is a private referral hospital serving two districts Kilombero and Ulanga 16. This hospital consists of various units including the Reproductive and Child Health Unit (RCH) where pregnant women attend clinic. It is among the hospitals in Ifakara town council offering the best antenatal care services making an influx of visitors either patients or clinic attendee to be a significant number 16. This study area was significant for obtaining information on dietary diversity and nutrition status among adolescent pregnant girls since it serves a huge population of around 800,000 people (St. Francis Referral Hospital Ifakara, n.d.)

2.1 Study Design

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study, whereby data were collected at one point in time.

2.2 Study Population

A representative number of adolescent pregnant girls aged 15-19 years attending the RCH clinic at SFRRH was included in the study. Adolescent pregnant women aged below 15 years were excluded since there is a high prevalence of pregnancies among the age group 15-19 years 17. Moreover, only participants who accepted and signed written informed consent were included.

2.3 Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

Purposive sampling was used to obtain a sample. The sample size was obtained using Cochran’s formula which is: n = , where Z is standard normal variance (1.95 for 95%), n is the desired sample size, p is the proportion of the target population estimated to have a particular characteristic, q is the proportion of the target population estimated not to have a particular characteristic and d is the degree of accuracy desired (0.05 of 5%) 18. The proportion of adolescent pregnant girls in Tanzania is 22%.

Hence, n =

= 261 adolescent pregnant girls

But due to limited time and resources the desired sample size was reduced by 50%.

Hence the desired sample size was 131 adolescent pregnant girls.

2.4 Data Collection

Qualitative and quantitative data were obtained using a structured questionnaire comprising four sections with demographic information, 24hrs dietary food recall information, anthropometric parameters and factors influencing dietary diversity and nutritional status respectively. Anthropometric data was obtained by measuring Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) using a MUAC tape. The questionnaire was written in English and then translated to Swahili language for easy understanding. During sessions with pregnant adolescent, the researcher was the one filling the questionnaire.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Data collected was coded and entered in SPSS version 20 then imported to R software version 4.4.0 for statistical analysis. Microsoft Excel software was utilized to generate charts and graphs for visualization purposes. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the demographic characteristics of the 131 adolescent pregnant women, including their age distribution, marital status, gravidity, educational background, and occupation. Dietary diversity was assessed using the minimum dietary diversity score calculated from 24-hour recall data. Chi-square tests were performed to examine the association between dietary diversity score, demographic variables, including age, marital status, gravidity, education level, and occupation, and socioeconomic and cultural factors. This test was used due to the presence of categorical variables such as demographic factors (age, marital status, education, and occupation), and its ability to assess the association of these variables with MUAC and dietary diversity score.

2.6 Ethical Approval

The ethical approval for conducting this research was obtained from the Institution Review Board at St Francis University College of Health and Allied Sciences.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic Information

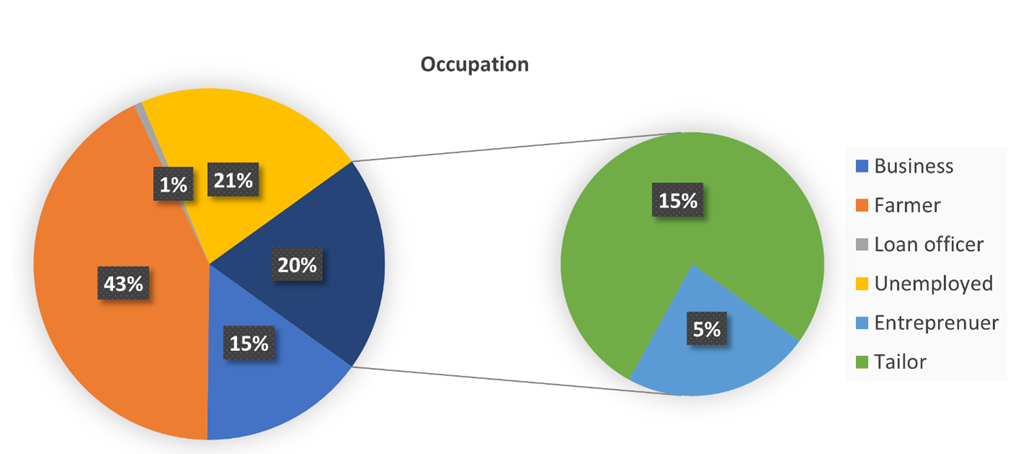

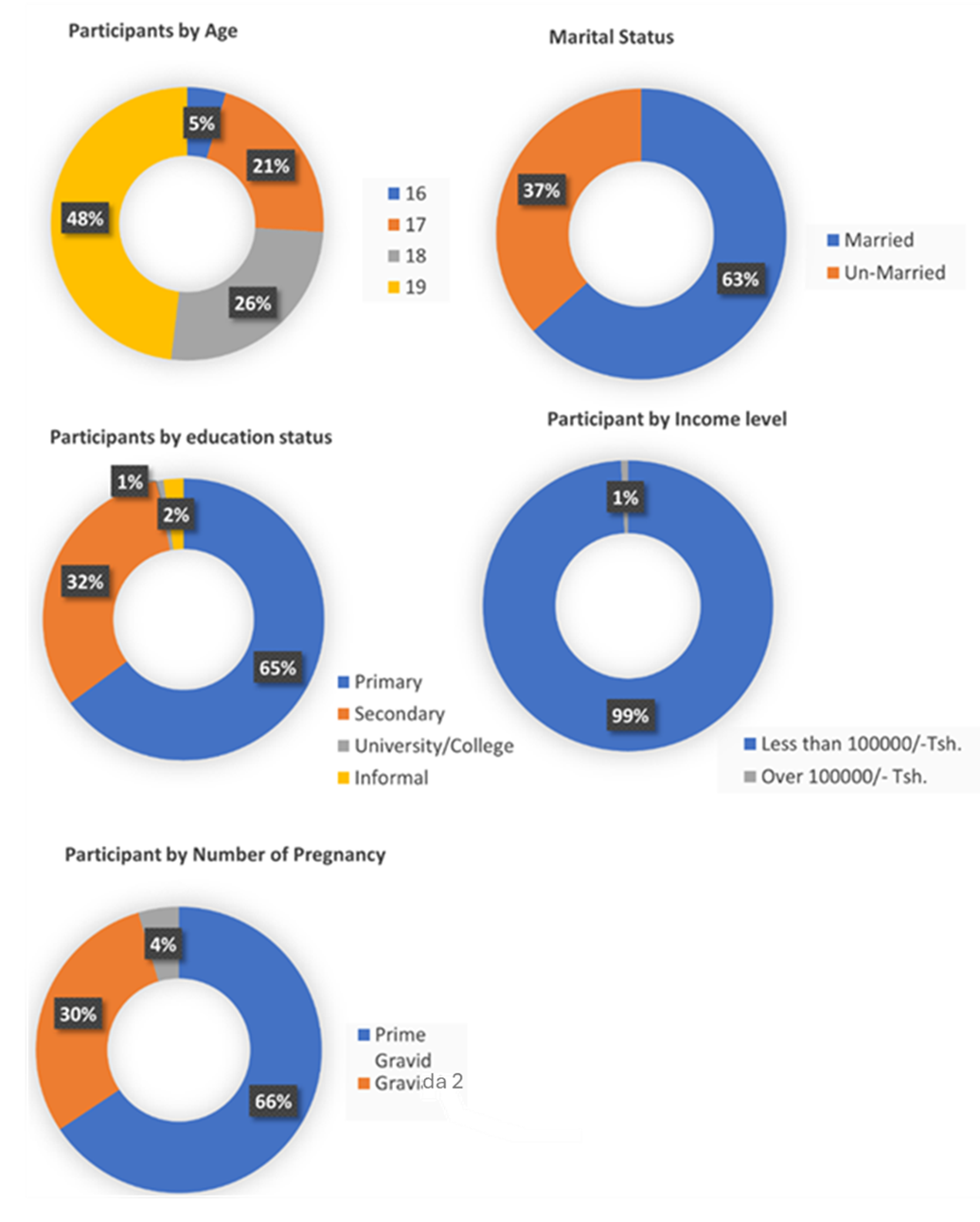

A total of 131 adolescent pregnant women aged 15-19 years participated in this study. The mean age of participants was (18 ± 0.9 SD) years. A large proportion aged 19 years (n=63, 48.1%), followed by 18 years (n=34, 26.0%), and the rest (n=34, 26.0 %) had 16-17 years. Majority of the women were married (n=83, 63.4%) while the rest (n=48, 36.6%) were unmarried. Regarding the gravidity (n= 86, 65.6%) were prime gravid while the rest (n=45, 34.4%) were gravida 2 and 3. Most of the women had primary education (n=85,64.9%) followed by secondary education (n=42,32.1%) and the rest (n=4,3.1%) had university and informal education (Figure 2). Moreover, majority of the participants were farmers (n= 56, 42.7%) followed by unemployed (n= 28, 21.4%) and the rest (n=47, 35.9%) were small business owners. Concerning their occupation, most women (n= 130, 99.2%) had an income less than Tshs.100,000/= (Figure 1).

3.2 Adolescent Pregnant Dietary Diversity

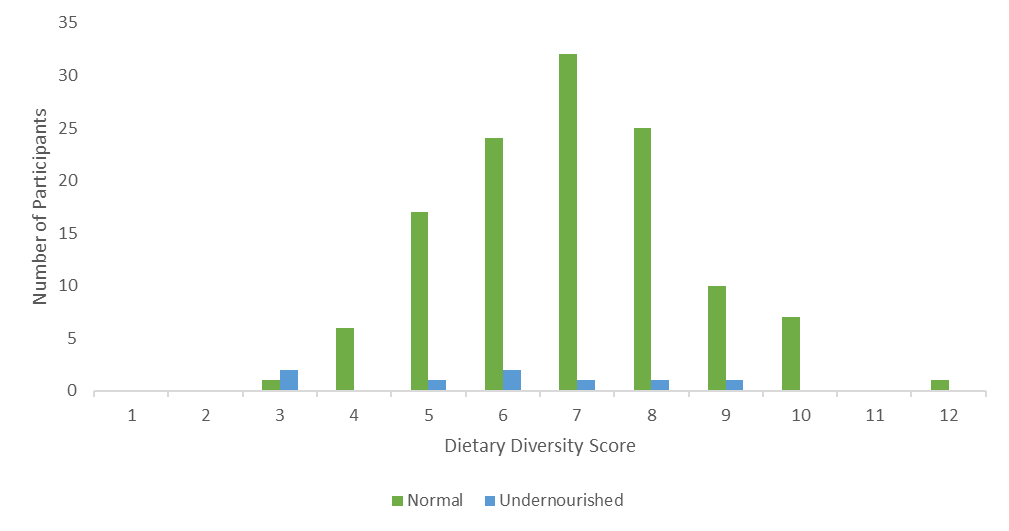

This study found that the mean DD score was 6 (SD = 1.65). Out of 131 adolescent pregnant women (n =122, 93.1%) met the minimum dietary diversity score about the 24-hour recall period. The proportion of dietary diversity was similar across the age of participants (χ1 2 = 31.78, p = 0.240), with the majority (n=122, 93.1%) meeting the minimum dietary diversity score. The proportion of dietary diversity score statistically differed with the number of children born (χ1 2 = 48.44, p < 0.001), with prime gravida (n =80, 93.0%) meeting most of the dietary diversity score compared to the rest. There was a statistically significant difference in the proportions of dietary diversity score with marital status (χ1 2 = 18.25, p = 0.032). With (n= 76, 91.6%) married and (n=46, 95.8%) unmarried adolescent pregnant women met the minimum dietary diversity score while (n=7, 8.4%) married and (n=2, 4.2%) unmarried failed to meet the minimum dietary diversity score on a 24-hour recall period. Moreover, the majority (n= 77, 90.5%) participants with primary education followed by (n= 42, 100%) secondary education and the rest (n= 2, 100%) university and informal education met the minimum dietary diversity score. This observed difference was statistically significant (χ1 2 = 74.67, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the DD score was similar across the participants’ occupations (χ1 2 = 43.047, p = 0.555) (Table 1).

3.3 Adolescent Pregnant Nutrition Status

Overall, out of 131 adolescent pregnant women (n =123, 93.9% and n= 8, 6.1%) fell under normal and undernourished MUAC category (Figure 3). The mean MUAC was 24 (SD = 2.37). The proportion of MUAC was similar across the age of participants (χ1 2 = 3.02, p = 0.389, Table 2). Similarly, the proportion of MUAC across the number of children born was not statistically significant (χ1 2 = 4.32, p = 0.115). Moreover, the proportion of MUAC across the marital status was not statistically significant (χ1 2 = 0.11, p = 0.744). Furthermore, the proportion of MUAC across education status was not statistically significant (χ1 2 = 0.53, p = 0.913). Additionally, the proportion of MUAC across participants’ occupations was not statistically significant (χ1 2 = 3.38, p = 0.642) (Table 2).

3.4 Adolescent Pregnant Dietary Diversity Score and Nutrition Status

Overall, out of 121 adolescent pregnant women who met the minimum dietary diversity score only (n= 115, 95.0%) had normal MUAC while the rest (n= 6, 5.0%) were undernourished (Figure 3). Moreover, out of 10 women who did not meet the minimum dietary diversity score, only (n= 8, 80.0%) had normal MUAC while the rest (n= 2, 20.0%) were undernourished. This observed difference was statistically significant (χ1 2 = 21.19, p = 0.012).

3.5 Factors Influencing Dietary Diversity Among Adolescent Pregnancy

Among the factors assessed to influence dietary diversity score nutrition knowledge provided at the health facility was observed statistically significant (χ1 2 = 25.016, p = 0.003). Moreover, women’s declaration of nutrition knowledge sufficiency was statistically significant as well (χ1 2 =24.46, p = 0.004). However, family and friend support was observed not to be statistically significant in influencing DD Score among pregnant adolescent women (χ1 2 = 35.24, p = 0.505). But also, additional resources to support women during pregnancy were observed not to be statistically significant (χ1 2 = 31.99, p = 0.928).

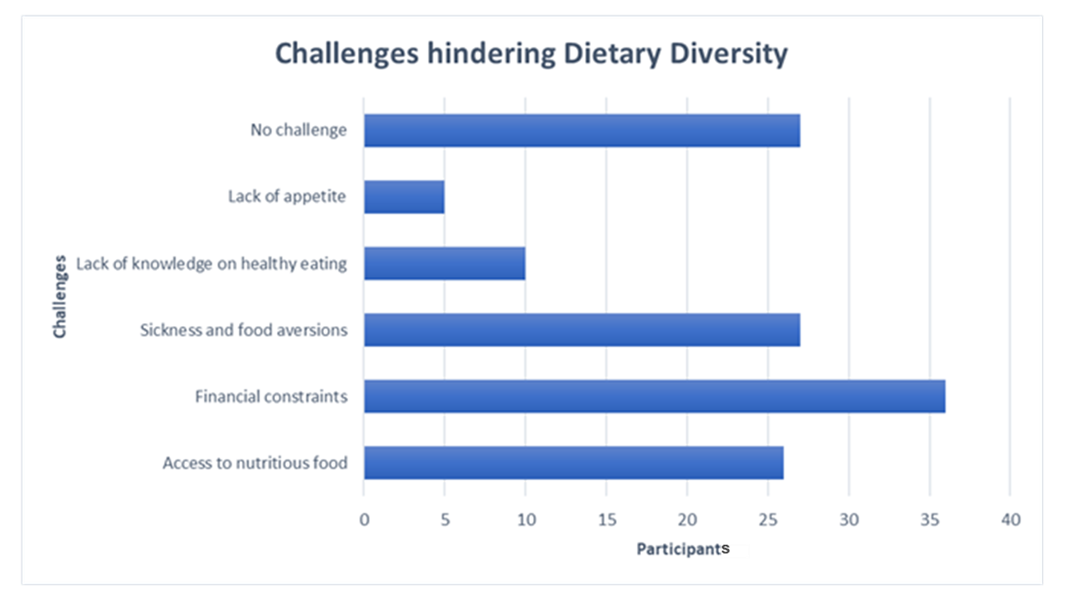

Several challenges were identified that hindered adolescent pregnant participants from maintaining a balanced diet. Majority of them (n= 36, 27.5%) stated that they failed to access recommended foods due to financial constraints. Moreover, some women (n= 32, 24.4%) complained of being sick, food aversions and lack of appetite therefore not preferring most foods hindering their diversity. Additionally, other women (n= 10, 7.6%) stated being ignorant of healthy eating while others (n= 27, 19.8%) mentioned lacking access to the recommended foods due to the resident setting and cultural limitations as well. However, other women (n=26, 20.6%) stated that they faced no challenge in meeting the recommended diet (Figure 4). These observed challenges associated with meeting the minimum dietary diversity score were marginally statistically significant (χ1 2 = 61.316, p = 0.053).

|

Factors |

|

Dietary diversity score |

p -value |

|

|

|

Total (n=131) |

Inadequate (<5) (n=9) |

Adequate (≥ 5) (n=122) |

|

|

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

0(0) |

0(0) |

0(0) |

|

|

16 |

6(4.6) |

0(4.9) |

6(5.0) |

|

|

17 |

28(21.4) |

0(22.8) |

28(23.0) |

|

|

18 |

34(26.0) |

4(25.2) |

30(24.6) |

|

|

19 |

63(48.1) |

5(47.2) |

58(47.5) |

0.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education Status |

|

|

|

|

|

Primary |

85(64.9) |

8(64.3) |

77(63.1) |

|

|

Secondary |

42(32.1) |

0(32.5) |

42(34.5) |

|

|

University/college |

1(0.8) |

0(0.8) |

1(0.8) |

|

|

Informal |

3(2.3) |

1(2.4) |

2(1.6) |

<0.001* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

Bena |

2(1.5) |

0(1.6) |

2(1.6) |

|

|

Chaga |

5(3.8) |

0(0) |

5(4.1) |

|

|

Hehe |

5(3.8) |

0(0) |

5(4.1) |

|

|

Ndamba |

14(10.7) |

0(0) |

14(11.5) |

|

|

Ndewe |

9(6.9) |

1(6.5) |

8(6.6) |

|

|

Ngindo |

25(19.1) |

3(19.5) |

22(18.0) |

|

|

Ngoni |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

1(0.8) |

|

|

Nyakyusa |

6(4.6) |

0(0) |

6(4.9) |

|

|

Pare |

5(3.8) |

0(0) |

5(4.1) |

|

|

Pogoro |

40(30.5) |

4(31.7) |

36(29.5) |

|

|

Sambaa |

4(3.1) |

0(0) |

4(3.3) |

|

|

Sukuma |

15(11.5) |

2(11.4) |

13(10.7) |

0.216 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Income level |

|

|

|

|

|

Less than 100,000/= |

130(99.2) |

9(99.2) |

121(99.2) |

|

|

Over 100,000/= |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

1(0.8) |

<0.001* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

83(63.4) |

7(62.6) |

76(62.3) |

|

|

Unmarried |

48(36.6) |

2(37.4) |

46(37.8) |

0.032 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of children |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

86(65.7) |

5(64.2) |

81(66.4) |

|

|

1 |

39(8) |

0(0) |

39(32.0) |

|

|

2 |

6(4.6) |

4(4.1) |

2(1.6) |

<0.001* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

Business women |

20(15.3) |

2(14.6) |

18(14.8) |

|

|

Farmer |

56(42.8) |

4(41.5) |

52(42.6) |

|

|

Loan Officer |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

1(0.8) |

|

|

No Job |

28(21.4) |

1(22.0) |

27(22.1) |

|

|

Entrepreneur |

6(4.6) |

0(0) |

6(4.9) |

|

|

Tailor |

20(15.3) |

2(16.3) |

18(14.8) |

0.555 |

|

Factors |

|

MUAC |

|

|

|

|

Total (n=131) |

Normal (n=123) |

Undernourished (n=8) |

p -value |

|

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

0(0) |

0(0) |

0(0) |

|

|

16 |

6(4.6) |

6(4.9) |

0(0) |

|

|

17 |

28(21.4) |

28(22.8) |

0(0) |

|

|

18 |

34(26.0) |

31(25.2) |

3(37.5) |

|

|

19 |

63(48.0) |

58(47.1) |

5(62.5) |

0.389 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education Status |

|

|

|

|

|

Primary |

85(64.9) |

79(64.2) |

6(75) |

|

|

Secondary |

42(32.1) |

40(32.5) |

2(25) |

|

|

University/college |

1(0.8) |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

|

|

Informal |

3(2.3) |

3(2.5) |

0(0) |

0.9129 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

Bena |

2(1.5) |

2(1.6) |

0(0) |

|

|

Chaga |

5(3.8) |

5(4.1) |

0(0) |

|

|

Hehe |

5(3.9) |

5(4.1) |

0(0) |

|

|

Ndamba |

14(10.7) |

13(10.6) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Ndewe |

9(6.9) |

8(6.5) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Ngindo |

25(19.1) |

24(19.5) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Ngoni |

1(0.8) |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

|

|

Nyakyusa |

6(4.6) |

5(4.1) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Pare |

5(3.9) |

3(2.4) |

2(25) |

|

|

Pogoro |

40(30.5) |

39(31.7) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Sambaa |

4(3.1) |

4(3.3) |

0(0) |

|

|

Sukuma |

15(11.5) |

14(11.4) |

1(12.5) |

0.3125 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Income level |

|

|

|

|

|

Less than 100,000/= |

130(99.2) |

122(99.2) |

8(100) |

|

|

Over 100,000/= |

1(0.8) |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

Married |

83(63.4) |

77(62.6) |

6(75) |

|

|

Unmarried |

48(36.6) |

46(37.4) |

2(25) |

0.744 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of children |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

86(65.6) |

79(64.2) |

7(87.5) |

|

|

1 |

39(29.8) |

39(31.7) |

0(0) |

|

|

2 |

6(4.6) |

5(4.1) |

1(12.5) |

0.1151 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

Business women |

20(15.3) |

18(14.6) |

2(25) |

|

|

Farmer |

56(42.7) |

51(41.5) |

5(62.5) |

|

|

Loan Officer |

1(0.8) |

1(0.8) |

0(0) |

|

|

No Job |

28(21.4) |

27(22.0) |

1(12.5) |

|

|

Entrepreneur |

6(4.6) |

6(4.9) |

0(0) |

|

|

Tailor |

20(15.3) |

20(16.3) |

0(0) |

0.6422 |

4 Discussion

This study sought to determine dietary diversity and nutrition status along with influencing factors such as socio-economic and demographic among adolescent pregnant. Given the dual nutritional demands faced by pregnant adolescents, understanding dietary patterns is crucial to ensuring they receive adequate nutrition, which in turn supports the health and well-being of both mother and child Although the sample size was reduced by 50%, the results are based on this reduced sample and show no impact on the significance of the findings.

The results reveal that approximately 93% of the participants met the Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women of Reproductive Age (MDD-W) during the 24-hour recall period, indicating that most adolescent pregnant women had access to a relatively diverse diet. Nutrition education, demonstrations, and counselling provided during monthly antenatal clinic visits likely contributed to this adherence to a diverse diet. This finding contrasts with a study in Tanzania by Heri et al. 19, which found that only 28% of pregnant women met the minimum dietary diversity score, largely due to limited nutrition education within the general population, underscoring the importance of nutrition education in promoting dietary diversity. Moreover, a study done by Mruma et al. 20 in Tanzania, revealed that some pregnant women fail to utilize the given nutritional information at the clinic, and thereafter fail to adhere to a diverse diet further posing risks of deficiencies and poor health outcomes.

Furthermore, several factors were identified to influence dietary diversity, including socio-demographic aspects such as age, education level, and marital status, as well as socio-economic factors like economic status and occupation. When analysing age in dietary diversity scores, the study found no significant differences across age groups, suggesting that age does not substantially impact dietary diversity. However, studies in Ethiopia suggested that younger pregnant women under 20 years old may adhere better to dietary diversity guidelines due to their lack of experience compared to older women 14. Therefore, it can be evident that the younger a woman is the more she adheres to the guideline but also considering the number of children born of the mother also could entail adherence level.

The results indicated that dietary diversity was different depending on gravidity, with primigravida women (those pregnant for the first time) more likely to achieve the minimum dietary diversity score compared to multiparous women (those with more than one child). This largely is attributed to novice pregnancy experience that constricts these mothers to listen and follow their health instructor to ensure better nutrition and their well-being during the pregnancy period. A study done in Somalia also reported that primigravida women had a better adherence to diverse diets per direction contributing to their nutritional status 15. Similarly, a study from Eastern Ethiopia suggested that first-time mothers often have more resources and support, which may facilitate better dietary practices compared to women who have had multiple pregnancies 21. These findings highlight the importance of considering parity when addressing dietary diversity in pregnant women.

Additionally, marital status significantly influenced dietary diversity, with a significant difference observed between married and unmarried women. Married women have their husbands’ support emotionally and physically as well, this greatly gives assurance and psychological support that is essential during the time 22. This finding aligns with a study done in Ethiopia, which found that marital status had a more substantial impact on dietary diversity, possibly due to social support systems involved 14.

Moreover, educational status was a notable factor in dietary diversity, with women who had at least a secondary education showing better adherence to diverse diets. This can be attributed to their enhanced understanding of the importance of nutrition. This finding aligns with a study done in Western Ethiopia, which emphasized the role of education in fostering nutritional knowledge and making healthier dietary choices 23. Conversely, occupation did not have a significant impact on dietary diversity, suggesting that regardless of employment status, women had equal opportunities to maintain a diverse diet. This may be because most women had similar occupations of peasantry as the study took place in a rural setting. Moreover, access to the same food markets purchasing the same kind of food items, along with societal norms regarding dietary practices during pregnancy. However, this finding contrasts with a study done in Nepal, which found that employment status significantly influenced dietary diversity due to increased income, which allowed for better food access 24. The interplay between education and occupation highlights the complex nature of dietary diversity determinants.

Furthermore, this study found a significant correlation between nutritional status, as measured by Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC), and dietary diversity score, highlighting the crucial role of dietary diversity in maternal nutrition. This supports findings from a study in Kenya, which argued that dietary diversity is closely linked to nutrient adequacy and improved maternal nutritional status 25. Similarly, A study done in Ethiopia indicated that dietary diversity positively impacts both maternal and fetal health 14. Therefore, it is essential for pregnant women, particularly adolescents, to ensure they consume a diverse diet to meet their increased nutritional needs and support fetal development, leading to better health outcomes for both mother and baby.

Moreover, while socio-economic and demographic factors did not significantly account for nutritional status as measured by MUAC, studies from Western Ethiopia and Indonesia have shown that these factors can significantly influence nutritional status through the adoption of good dietary practices 26, 23. Despite this contradiction with other research on the influence of these factors, they remain crucial for ensuring the health of both mother and fetus. Additionally, maintaining good nutritional status is vital for infant health, particularly given the increased nutrient requirements of adolescent mothers. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive approaches to maternal nutrition.

As well, nutrition knowledge provided at health facilities and participants' self-reported nutrition knowledge was significantly associated with higher dietary diversity. This finding is consistent with a study done in Tanzania, that highlighted the critical role of nutrition education in improving dietary outcomes 19. Moreover, a study done in Ethiopia also revealed the positive impact of nutrition knowledge given at antenatal clinics on improving dietary diversity 27.

Not only that but also, family and friend support, as well as additional resources for pregnant women, were not significantly associated with dietary diversity scores. This can be attributed to the fact that most women reported having less support from family and friends since most self-supported themselves, but also required no additional resources or support, due to acknowledgement of clinic support being sufficient. Al-Mutawal et al. nailed the significant factor of social support to enhance the well-being of pregnant women hence contributing to overall health outcomes 28. These contrasts suggest that while nutrition education is pivotal, social support mechanisms should not be overlooked as it may lead to psychological support hence avoiding the risk of depression, which may result in incidences such as miscarriage 28, 29.

Additionally, financial constraints, health issues such as illness, food aversions, lack of appetite, ignorance about healthy eating, lack of access to recommended foods due to residential settings, and cultural restrictions were identified as challenges hindering dietary diversity among adolescent pregnant women. Although these challenges were only marginally statistically significant, addressing them could potentially improve dietary diversity in this population. Similar barriers were reported where the emphasis was on the importance of overcoming socioeconomic and educational barriers to enhance dietary practices 24, 30.

This study was hospital-based, with the sample size being reduced by 50% due to practical constraints of time and funds, hence may not fully reflect the dietary diversity of adolescent women in the broader community. Additionally, the study's cross-sectional design and reliance on a 24-hour dietary recall period recorded on random days may not capture the full variability in daily food consumption, but also as individuals attending hospitals may tend to have higher education levels or income than those in the general population, this may have potentially introduced biases and affect the generalizability of the findings.

The findings of this study revealed that most adolescent pregnant women were able to achieve adequate dietary diversity. However, socio-demographic factors such as age, occupation, and education, along with challenges like loss of appetite and illness, influenced both their dietary diversity and overall nutritional status. Therefore, in order to improve dietary outcomes, it is essential to address these challenges. Furthermore, future research should take a community-based longitudinal approach to better understand how these factors impact dietary patterns among adolescent pregnant women. This could lead to the development of targeted interventions aimed at promoting positive health outcomes for both mothers and their new-borns.

List of Abbreviations

DC: District Council, DD Score: Dietary Diversity Score, MC: Municipal Council, MUAC: Mid Upper Arm Circumference, RCH: Reproductive and Child Health, SFRRH: St Francis Regional Referral Hospital, and TC: Town Council.

Acknowledgement

My sincere gratitude to the Almighty God who has given me the strength perseverance and resilience to perform this work up to the very end. Moreover, I would like to thank the director at St Francis Referral Hospital for granting permission to perform this study at the facility along with all the study participants. Also, my sincere gratitude extends to my family for their genuine support that I can’t afford to repay with prayers to make this work a success. Last but not least, I would like to thank my mentor who has been a huge support throughout this journey.

Author’s Contribution

Author 01 and Author 02 designed and conceptualized the study, drafted the manuscript, engaged in data collection, entry, and analysis, and also prepared the initial manuscript. Author 02 provided supervision, revised the manuscript, engaged in data analysis, and was involved in writing and approving the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.