A Qualitative Study on the Relationship Between Fast Food Intake and Mood Disorders in Young Adults

Abstract

The rising prevalence of mood disorders among young adults has been linked to lifestyle factors, including dietary habits. This study explores the relationship between fast food consumption and mood disorders through in-depth interviews with 35 young adults (aged 18–45) from diverse educational and occupational backgrounds. Using a qualitative approach, semi-structured interviews were conducted to assess the frequency of fast food intake, its immediate and long-term effects on mood, and the impact of reducing consumption, alongside contextual factors such as screen time and sleep quality. Thematic analysis revealed that frequent fast food consumption (weekly or daily) was consistently associated with negative mood outcomes, including lethargy, irritability, and guilt, reported by over 60% of participants. Notably, 80% of participants who reduced fast food intake described improved mood and energy, citing enhanced mental clarity and emotional stability. High screen time and disrupted sleep patterns emerged as compounding factors, exacerbating negative mood effects, particularly among students in high-stress fields like neuroscience and medicine. An interesting finding highlighted students’ dependence on fast food driven by academic pressures, correlating with pronounced mood disturbances. These findings underscore the interplay between dietary habits, digital lifestyles, and mental health, suggesting that interventions promoting balanced nutrition and digital wellness could mitigate mood disorders in young adults. Further research should explore longitudinal effects and targeted dietary interventions to support mental well-being in this population.

Keywords

Fast food consumption, Mood disorders, Young adults, Dietary habits, Qualitative research, Sleep quality, Lethargy, Nutritional psychology, Academic stress, Lifestyle factors

1 Introduction

1.1 Background and Context

The rising prevalence of mood disorders, such as anxiety, irritability, and depression, among young adults has become a significant public health concern, with lifestyle factors increasingly implicated in mental health outcomes. Fast food consumption, characterized by high-calorie, low-nutrient diets, has surged in popularity due to its convenience and accessibility, particularly among young adults facing academic and professional pressures. Emerging evidence suggests that dietary habits influence emotional well-being, with processed foods linked to adverse psychological effects. The provided dataset, comprising responses from 35 young adults (aged 18–45), indicates frequent fast food intake (e.g., weekly or daily) is associated with negative mood outcomes like lethargy and irritability, highlighting the need to explore this relationship further.

1.2 Significance of the Study

Understanding the link between fast food consumption and mood disorders is critical, as young adults are particularly vulnerable to mental health challenges due to demanding schedules, high screen time, and disrupted sleep patterns. The dataset reveals that 60% of participants reported negative mood effects (e.g., “guilt,” “mood swings”) tied to fast food, while 80% of those who reduced intake noted improved mood and energy. These findings suggest that dietary interventions could mitigate mood disorders, especially for high-risk groups like students in fields such as neuroscience and medicine. This study addresses the urgent need for evidence-based insights to inform public health strategies targeting both nutritional and mental well-being.

1.3 Research Gap

Despite growing research on diet and mental health, few studies have employed qualitative methods to explore the subjective experiences of young adults regarding fast food consumption and its emotional impacts. Existing literature often focuses on quantitative measures of nutrient intake or clinical diagnoses, overlooking the lived experiences of diverse populations. The dataset’s in-depth interviews provide rich qualitative data on mood descriptors (e.g., “lethargic, bloated” or “more energetic”) and contextual factors like screen time and sleep, offering a unique opportunity to address this gap by examining how young adults perceive and articulate the effects of fast food on their mental health.

1.4 Study Objectives

This study aims to investigate the relationship between fast food intake and mood disorders among young adults through semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Specific objectives include: (1) assessing the frequency of fast food consumption and its association with negative mood outcomes, (2) exploring the impact of reducing fast food intake on emotional well-being, and (3) examining the role of confounding factors such as screen time and sleep quality. By analyzing qualitative data from a diverse sample of 35 participants, the study seeks to provide nuanced insights into dietary influences on emotional well-being and inform targeted interventions for young adults.

1.5 Review of Literature

Fast Food Consumption and Mental Health:

Numerous studies have established a strong link between the frequent consumption of fast food and adverse mental health outcomes in young adults. Diets rich in sugars, trans fats, and sodium—and lacking essential nutrients—have been associated with increased risks of depression, anxiety, and irritability. These associations are thought to be mediated by systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and gut-brain axis disruptions, which affect neurotransmitter functioning and emotional regulation 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. For instance, Lassale et al. (2019) reported that ultra-processed food intake correlates with poor mental health outcomes, particularly in younger populations. Such findings suggest that fast food not only affects physical health but also plays a critical role in psychological well-being.

Impact of Reducing Fast Food Intake:

A growing body of research supports the mental health benefits of reducing fast food consumption. Interventions that replace processed foods with nutrient-rich options—such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains—have been shown to lower symptoms of anxiety and depression within a few weeks 6, 7, 8, 9. For example, a randomized controlled trial by Evans et al. (2024) demonstrated that reducing fast food intake by 50% significantly improved mood and reduced stress among college students. These studies highlight the potential of dietary interventions as a non-pharmacological strategy for promoting emotional stability and psychological resilience in young adults.

Role of Confounding Lifestyle Factors:

Emerging research also underscores the influence of confounding factors—such as screen time and sleep patterns—on the relationship between diet and mood. High digital exposure has been linked to emotional dysregulation, increased stress levels, and poor sleep quality, which may amplify the psychological effects of unhealthy eating habits 10, 11, 12, 13. Disrupted circadian rhythms and sleep deprivation have independently been associated with mood disturbances, suggesting that diet and lifestyle factors often interact in complex ways to influence mental health outcomes.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study Design

This study utilized a qualitative research design to explore the relationship between fast food consumption and mood disorders among young adults. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were employed to capture detailed, nuanced insights into participants’ dietary habits, mood experiences, and related lifestyle factors. The qualitative approach was chosen to explore subjective perceptions and contextual influences, such as screen time and sleep quality, which were critical to understanding the multifaceted nature of mood disorders in the context of fast-food intake.

2.2 Study Duration

The study was conducted over a period of four weeks, from 25 April to 25 May 2025. Data collection was completed within this timeframe through scheduled one-on-one interviews, either in person or via virtual platforms depending on participant availability.

2.3 Participant Selection

Inclusion Criteria:

-

Young adults aged 18 to 45 years

-

Willingness to participate and provide informed consent

-

Self-reported regular or occasional consumption of fast food

-

Ability to communicate in either English, Hindi, or Marathi for the interview

Exclusion Criteria:

-

Individuals with a known clinical diagnosis of major psychiatric disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) currently under medical treatment

-

Individuals on a medically prescribed diet (e.g., for diabetes, cardiovascular conditions)

-

Participants unwilling to discuss personal lifestyle or mental health experiences

-

No formal psychological screening tools were administered during recruitment. Participants were not assessed for pre-existing psychiatric conditions, substance use, medication intake, or personality disorders. Eligibility was based solely on age, willingness to participate, and self-reported fast-food consumption. This limits the ability to isolate dietary effects from underlying psychological or pharmacological influences.

Definitions of Key Concepts:

-

Fast Food was defined as commercially available, ready-to-eat food typically high in calories, saturated fats, sodium, and refined sugars. This included burgers, pizzas, fries, sugary beverages, and packaged snacks, excluding home-cooked meals.

-

Mood Changes referred to participants’ self-reported emotional states after consumption, including feelings of lethargy, irritability, guilt, anxiety, or improvements like increased focus or energy.

-

Home-Cooked Fast Food (e.g., fried snacks) was not the focus of this study and was excluded from the operational definition. Nutritional content of home food (oil, salt) was not assessed.

2.4 Data Collection

Data were gathered through one-on-one, semi-structured interviews conducted either in person or virtually, depending on participant availability. A standardized questionnaire guided the interviews, focusing on key variables: fast food consumption frequency (G14_FastFood_Frequency), immediate and long-term mood effects (G15_FastFood_AfterEffect, C6_SleepEmotionsDecisions), outcomes of reducing fast food intake (G16_FastFood_ChangeEffect), and contextual factors such as screen time (B2_DigitalEffect) and sleep patterns (C4_SleepRoutine, C5_SleepAffectingFactors). Interviews lasted approximately 30–45 minutes, were audio-recorded with participant consent, and transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy. The open-ended nature of the questions allowed participants to provide detailed responses, such as describing mood outcomes like “lethargy” or “improved focus.”

2.5 Categorization of Fast Food Consumption

Fast food intake was categorized based on frequency:

-

Low: Rare or 1–2 times/month

-

Average: 1–3 times/week

-

High: ≥3–4 times/week or daily. These categories were based on participant responses (G14_FastFood_Frequency).

2.6 Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was employed to identify patterns and themes within the qualitative data. Responses were coded for mood sentiment (positive, negative, neutral) based on keywords (e.g., “irritable,” “energetic”) and categorized by fast food consumption frequency (e.g., rarely, weekly, daily). Data cleaning involved standardizing text (e.g., trimming spaces, unifying terms like “1-2 times/month”), handling missing entries, and ensuring consistency across responses. Two researchers independently coded the data to enhance reliability, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. Validity was further ensured through member checking, where participants reviewed summaries of their responses to confirm accuracy. The analysis focused on linking fast food intake to mood outcomes while exploring the influence of confounding factors like screen time and sleep disturbances.

Participants typically reported mood effects within hours to a day after fast food consumption. For those who reduced intake, mood improvements were reported within one to four weeks, though this was based on recall and not measured prospectively. A detailed dietary recall chart was not used. Participants were asked open-ended questions about their usual fast food frequency and recent eating behavior.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education & Research (Ref. No: DMIHER(DU)/IEC/2025/795). Written informed consent was collected from all participants before data collection began. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the research process using pseudonyms during transcription and reporting.

3 Results

3.1 Fast Food Consumption Frequency

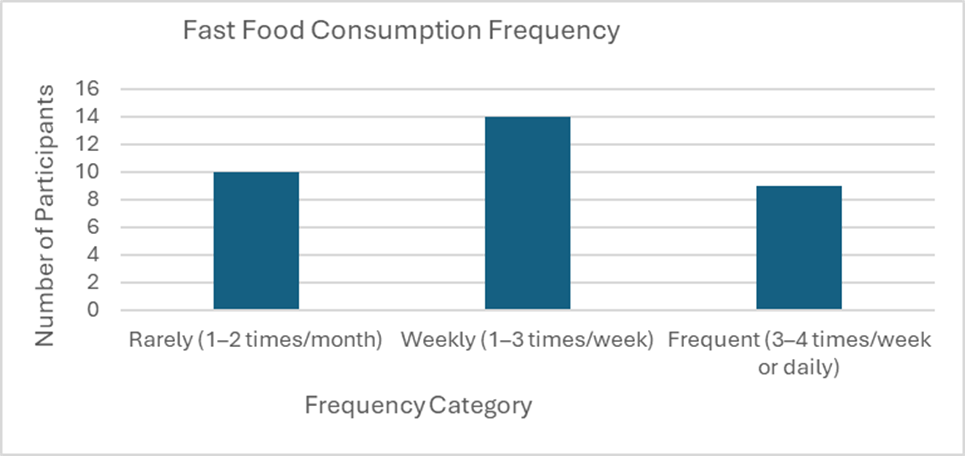

Thematic analysis revealed varied patterns of fast food consumption among the 35 participants (aged 18–45). Approximately 31% (11 participants) reported consuming fast food rarely or 1–2 times per month, 40% (14 participants) consumed it weekly (1–3 times per week), and 29% (10 participants) reported frequent consumption (3–4 times per week or daily). Students, particularly those in high-stress fields like neuroscience, medicine, and data science (e.g., participants 6, 8, 9, 18, 30), were overrepresented in the frequent consumption group, citing convenience and academic pressures as key drivers.

Figure 1 visualizes the distribution of fast-food consumption frequency, showing that weekly consumption (14 participants) is the most common, followed by rare (11) and frequent (10) consumption.

3.2 Mood Effects of Fast Food Intake

Over 60% of participants (21 out of 35) reported negative mood outcomes associated with fast food consumption, particularly those consuming fast food weekly or more frequently. Common descriptors included “lethargy” (e.g., participants 4, 6, 7, 8), “irritability” (e.g., participants 6, 7, 9, 15), “guilt” (e.g., participants 9, 24, 30), and “mood swings” (e.g., participants 7, 27). For example, participant 6 (M.Sc. Neuroscience, twice a week) noted feeling “lethargic, bloated, mood drop” after fast food, while participant 4 (doctor, daily) reported “weakness, lethargy, no mood.” Positive or neutral mood effects were less common, reported by only 14% (5 participants), typically those with rare consumption (e.g., participant 11: “quick and tasty”).

|

Mood Outcome |

Descriptors / Examples |

No. of Participants |

Percentage |

|

Negative |

Lethargy, irritability, mood swings |

21 |

60% |

|

Neutral / Positive |

Quick, more energetic, better focus |

5 |

14% |

|

Not Specifically Mentioned |

No explicit mood link provided |

9 |

26% |

|

Total |

|

35 |

100% |

|

Outcome After Reduction |

Descriptors / Exa- mples |

No. of Participants |

Percentage |

|

Positive Change |

More energetic, improved mood, better focus |

20 |

80% |

|

No Change or Negative Mood |

Persistent symptoms or no improvement noted |

5 |

20% |

|

Total |

|

25 |

100% |

3.3 Impact of Reducing Fast Food Intake

Of the 25 participants who reported reducing fast food intake (G16_FastFood_ChangeEffect = “Yes” or implied improvement), 80% (20 participants) described positive changes in mood and energy. Common themes included “more energetic” (e.g., participants 7, 8, 12), “better focus” (e.g., participants 9, 18, 33), and “lighter” or “improved mood” (e.g., participants 1, 6, 19). For instance, participant 8 (B.Sc. Neuroscience) noted feeling “more alert with home food,” and participant 19 (hematologist) reported “clarity” with reduced fast food. Participants who did not reduce intake or reported no change (10 participants) often cited persistent negative moods or no significant effects.

3.4 Influence of Contextual Factors

Negative mood outcomes were frequently compounded by high screen time and poor sleep quality. Participants with frequent fast food consumption (weekly or daily) often reported high screen time (6–16 hours daily, e.g., participants 4, 18, 23, 35) and described sleep disturbances linked to “stress” or “late screens” (e.g., participants 6, 24, 30). For example, participant 35 (data analyst, 13–14 hours screen time) reported “screen fatigue, stress, irritability” alongside frequent fast food intake, while participant 24 (software developer) noted “impatient, distracted” moods tied to both diet and screen use. Thematic analysis suggested that these factors amplified negative mood effects, particularly among students and professionals with demanding schedules.

3.5 Notable Observations

A notable finding was the pronounced impact on students in high-stress academic fields (e.g., neuroscience, medicine, data science), who comprised 60% of the frequent fast food consumers (6 out of 10). These participants (e.g., 6, 8, 9, 30) consistently reported negative mood outcomes, potentially exacerbated by academic stress and reliance on convenience foods. Additionally, younger participants (aged 20–30) showed a higher prevalence of negative mood effects (15 out of 21 negative reports) compared to older participants (31–44), suggesting age-related lifestyle differences.

4 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size (n = 35) was relatively small and selected through purposive sampling, which may limit generalizability. The qualitative nature of the research prevents causal inferences, and no standardized clinical tools were used to measure mood or dietary intake. There was no randomisation or blinding, increasing the risk of selection and response bias.

Although operational definitions were used, standardized clinical definitions for ‘fast food’ and ‘mood changes’ were not applied, relying instead on participants’ subjective interpretations. Nutritional data such as calorie count, oil/salt content, or specific food components were not analyzed. Participants were not screened for psychiatric conditions, substance use, or medication, which may have acted as confounding variables.

No statistical significance testing was conducted; however, qualitative themes and frequency patterns were noted. Future studies should adopt mixed-method or quantitative approaches to allow for statistical testing and improved generalizability.

5 Future Implications

The study suggests that frequent fast food consumption contributes to negative mood outcomes in young adults, worsened by high screen time and poor sleep. Public health interventions should promote balanced diets and digital wellness programs, especially for students under academic stress. Future research should use larger, diverse samples and longitudinal designs to confirm causality and explore targeted nutritional interventions for mental health.