INTRODUCTION

Scheduled tribes have primitive traits, possess a unique culture, experience geographic isolation, demonstrate reluctance to engage with the general population, and display socio-economic underdevelopment. Consequently, they face many challenges, including social, religious, educational, and health-related issues. The tribal literacy rate in India is 58.96 percent[16]. It is very much lower when compared to the total literacy rate of India, which is 74.4 percent. Indigenous populations believe in and worship supernatural beings and powers. This created several doubts among young, educated individuals. Tribal cultures are experiencing profound shifts when they engage with other civilisations. In many aspects of their social existence, tribal communities resemble Western civilisation, while neglecting their indigenous traditions. Child marriage among tribes, infanticide, homicide, animal sacrifice, black magic, bride swapping, and other harmful traditions are regarded as significant societal issues confronting tribal populations in India. The principal sources of tribal income are hunting, gathering, and agriculture. Consequently, their per capita income is markedly inferior to that of the overall population. Many tribal communities are indebted to local moneylenders and zamindars.

Several tribal land laws exist to safeguard tribal lands from external encroachment. This work analyses the basic components and obstacles of the Forest Rights Act of 2006 (FRA 2006) in Kerala. The FRA attempts to restore land rights for tribal and traditional forest dwellers; however, its implementation faces challenges related to the recognition of community rights, the extent of land rights, and ongoing coordination with local development programs. The FRA seeks to rectify historical injustices experienced by forest-dwelling communities through the legal recognition of their traditional rights. The enactment of the FRA has a profound impact on the livelihoods, traditions, and future of forest communities in India. This paper employs Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and Nancy Fraser’s theory of Social Justice as analytical frameworks to interpret the implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in India. Sen’s Capability Approach emphasises the expansion of individuals’ freedoms and real opportunities to lead lives they value, thereby highlighting the importance of enabling forest-dwelling communities to exercise substantive choices over their livelihoods, cultural practices, and ecological stewardship. Complementing this, Fraser’s multidimensional theory of justice—encompassing redistribution, recognition, and representation—provides a critical lens to assess the structural and institutional barriers that affect the equitable realisation of forest rights. Together, these theoretical perspectives offer a comprehensive understanding of how the FRA functions not merely as a legal instrument but as a vehicle for advancing social justice and enhancing the capabilities of historically marginalised communities.

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

This paper analyses the historical reasons for the alienation of forest land from tribal communities and the impact of the FRA on their lives and livelihoods. The main objective of the FRA is to restore tribal’s customary rights, stop the historical injustice they had experienced over land dispossession. Secondly, the paper discusses the role of administrative-level committees for executing the FRA. Several key players have a role in implementing the FRA, including the Forest Rights Committee (FRC), Gram Sabha, Sub-Divisional Level Committee, District Level Committee (DLC), and State Level Monitoring Committee (SLC). The study assesses the impact of the FRA on forest conservation. Communities are encouraged to manage forests responsibly when they have secure tenure, which improves biodiversity and climate resilience. Additionally, this paper examines the challenges of implementing the Act, with administrative apathy being one of the major obstacles. The minimal role of the forest department and the state government’s unwillingness contribute to the important hurdles in implementing the Act.

METHODOLOGY

This study employs a qualitative research methodology, drawing extensively on secondary data sources to investigate the stated research objectives. The secondary data utilised in this analysis were obtained from a diverse range of credible materials, including official government policies, published government reports, reputable news journals, scholarly books, and peer-reviewed research articles. These sources provided a comprehensive foundation for understanding the multifaceted dimensions of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) and its implementation. Quantitative data pertaining to the number of claims received, titles distributed, claims rejected, disposed of, and those still pending across India—as of 31 May 2025—were retrieved from the official website of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA). This dataset serves as a critical empirical basis for evaluating the progress, bottlenecks, and administrative efficacy of FRA implementation at the national level.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE STUDY

Amartya Sen's capability approach and Nancy Fraser's theory of social justice provide strong foundations for evaluating and improving the Forest Rights Act's (FRA) implementation in India.

The Capability Approach of Amartya Sen: The Capability Approach of Amartya Sen can be applied in the framework of the FRA because the FRA is considered a legal and policy technique to expand the real freedom and capabilities of forest-dwelling communities. The Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006 and Amartya Sen's Capability Approach are similar in that they both focus on promoting individual and community freedoms, agency, and dignity, particularly for underserved forest-dwelling communities. Sen's concept emphasises how crucial it is to take down obstacles that stand in the way of turning rights into real capabilities. This lens can be used to examine the implementation issues of the FRA, including social inequality, bureaucratic roadblocks, and ignorance, to determine how these obstacles restrict the growth of true freedoms. Enhancing fundamental freedoms—what individuals may do and be—is at the heart of Sen's capability approach, which is crucial for assessing how the FRA affects tribal and forest inhabitants. The Act seeks to enable historically marginalised communities to exercise more agency and secure vital capabilities like livelihood, cultural preservation, and participation in local governing structures like Gram Sabha by establishing individual and community forest rights. One way to define capability is as a person's capacity to perform specific tasks. However, when a person is deemed capable, it allows him to live a life of dignity. There are both theoretical and practical issues that come up during the development process. Achieving a better quality of life is essential to development. Establishing regulations, creating jobs, and offering free food and education are some of the ways the government seeks to promote economic equality and development, but the main concern is whether the people can profit from a state policy[15].

Social Justice Theory of Nancy Fraser: The multifaceted framework of Nancy Fraser's social justice theory explores the cultural and economic aspects of injustice, highlighting the necessity of both acknowledgement and redistribution to attain true social justice. Fraser contends that failure to acknowledge cultural identities and social standing is just as much a part of social injustice as the unequal allocation of resources. An extensive framework for evaluating FRA is given by Nancy Fraser's three-dimensional theory of justice, which consists of representation (political), recognition (cultural), and redistribution (economic). Through the restoration of land and resource rights, recognition of traditional identities of tribal communities, and participation through participatory mechanisms such as Gram Sabhas, the Act aims to address redistribution. However, Fraser emphasises that improvements run the risk of escalating inequality if effective involvement and correcting underlying misrecognition are not addressed. Fraser's main normative tenet is "participatory parity," which states that social structures should allow everyone to engage with one another on an equal basis. Full involvement necessitates both the intersubjective (cultural awareness) and objective (economic equality) requirements.

While active Gram Sabha discussions and gender inclusion requirements are positive developments, "parity of participation" is still being threatened by power disparities, persistent exclusion, and opposition from government organisations and business interests. By recognising the identity and cultural rights of tribal and forest-dwelling communities, the FRA corrects historical injustices. It aims to use resource and land rights to address economic marginalisation. Also, the inclusive governance, in which underrepresented voices are not only heard but also can make decisions, is necessary for effective implementation. To secure institutional change that eliminates fundamental inequities, Fraser's paradigm exhorts policymakers to move beyond tokenistic inclusion.

TRIBAL LAND RIGHTS IN INDIA

The land is an important part of tribal life. The British intervention in the tribal areas to exploit natural resources in India instigated land alienation among the tribes. Furthermore, zamindars and merchants usurped tribal territory through the provision of loans and similar methods. The establishment of mines and several enterprises in the tribal territory provided wage labour and employment prospects in manufacturing. Consequently, the indigenous populations endure hardship when external entities exploit their resources and land. The lack of documentation among many tribal communities, who have lived in the forest for generations, has intensified the ongoing situation. The enforcement of the Forest Rights Act in 2006 fostered a prevalent perception that such legislation contributed to deforestation. The Forest Rights Act substantially transferred authority to Gram Sabhas and democratised the ownership of forest resources, land, and related matters. This scenario could be altered by several sections of these amendments. The primary means of subsistence for tribal communities is the forest and its resources; numerous tribes, particularly women, rely heavily on forest goods for agriculture, foraging, and hunting.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE FOREST RIGHTS ACT

The most important right of tribal people is their right to occupy and use their land. Land rights claims make emotive demands for material resource redistribution and acknowledge a distinct identity. Although strong laws are in place to formally support these rights, they have never been applied more than periodically, and even then, there is significant diversity between states and even between regions within states. Nonetheless, legal rights continue to be substantial driving factors for movements aiming to see them put into practice[18]. The land rights and livelihoods of the most marginalised and voiceless communities have been severely impacted by the historically exclusionary approach of mainstream conservation initiatives in India and beyond. Indigenous populations and other forest dwellers can and ought to serve as natural allies in conservation efforts, and the injustice of this approach has been widely recognised in contemporary society.

Tribals and forest-dwelling communities have always advocated their rights to forest land, culminating in the passing of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in 2006. Governments disregarded the rights of indigenous communities during the merging of state forests, leading to the enactment of the Forest Rights Act as a redress for this historical injustice. The FRA seeks to recognise the contributions of tribal and other indigenous forest inhabitants to conservation efforts. This legislation is referred to as the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, the Tribal Rights Act, or the Tribal Land Act. Scheduled tribes and other traditional forest residents are granted the right to possess and exploit forest property via individual or community ownership. Section 4(5) of the FRA forbids the eviction or removal of Scheduled Tribes or Traditional Forest Dwellers from their occupied forest land until recognition and verification are complete. Section 5 of the FRA empowers the Gram Sabha to ensure the enforcement of decisions regarding the regulation of access to communal forest resources and the cessation of acts detrimental to biodiversity, forests, or wildlife[11]. The nationwide execution of the FRA commenced in 2008, bolstered by civil society involvement, bureaucratic influence, and unwavering political will. States formulated action plans, formed legally mandated authorities, allocated financial and human resources, trained officials and frontline personnel of pertinent government departments, conducted awareness campaigns, and disseminated enabling circulars, orders, and supplementary materials. The procedure was meticulously and consistently monitored at multiple levels. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) has shown commendable adaptability and responsiveness, facilitating an accelerated rights recognition procedure. Most states effectively acknowledged individual forest rights. State agencies, district administrations, and civil society organisations formulated new methods to recognise individual and community rights and enable post-rights management of forests[21].

| Sl. No. | States | No. of Claims received Upto 31.05.2025 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Community | Total | ||

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh | 2,85,098 | 3,294 | 2,88,392 |

| 2 | Assam | 1,48,965 | 6,046 | 1,55,011 |

| 3 | Bihar | 4,696 | 0 | 4,696 |

| 4 | Chhattisgarh | 8,90,220 | 57,259 | 9,47,479 |

| 5 | Goa | 9,757 | 379 | 10,136 |

| 6 | Gujarat | 1,83,055 | 7,187 | 1,90,242 |

| 7 | Himachal Pradesh | 4,883 | 683 | 5,566 |

| 8 | Jharkhand | 1,07,032 | 3,724 | 1,10,756 |

| 9 | Karnataka | 2,88,549 | 5,940 | 2,94,489 |

| 10 | Kerala | 44,455 | 1,014 | 45,469 |

| 11 | Madhya Pradesh | 5,85,326 | 42,187 | 6,27,513 |

| 12 | Maharashtra | 3,97,897 | 11,259 | 4,09,156 |

| 13 | Odisha | 7,01,148 | 35,024 | 7,36,172 |

| 14 | Rajasthan | 1,13,162 | 5,213 | 1,18,375 |

| 15 | Tamil Nadu | 33,119 | 1,548 | 34,667 |

| 16 | Telangana | 6,51,822 | 3,427 | 6,55,249 |

| 17 | Tripura | 2,00,557 | 164 | 2,00,721 |

| 18 | Uttar Pradesh | 92,972 | 1,194 | 94,166 |

| 19 | Uttarakhand | 3,587 | 3,091 | 6,678 |

| 20 | West Bengal | 1,31,962 | 10,119 | 1,42,081 |

| 21 | Jammu & Kashmir | 33,233 | 12,857 | 46,090 |

| TOTAL | 49,11,495 | 2,11,609 | 51,23,104 | |

(Source: Ministry of Tribal Affairs, 2025 [12])

As of May 31, 2025, the data on claims and distribution of title deeds under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, reveals significant variation across states and Union Territories in India. Chhattisgarh recorded the highest number of claims, totalling 947,479, encompassing both individual and community rights. This reflects the state's proactive engagement with forest-dwelling communities and the extensive presence of tribal populations reliant on forest resources. Odisha follows with 736,172 claims, also

spanning individual and community levels, indicating substantial mobilisation around forest rights in the region. In contrast, Uttarakhand reported the lowest number of claims, with only 6,678 submissions. This disparity may be attributed to differences in forest cover, tribal demographics, administrative outreach, and awareness of the FRA provisions. The data underscores the uneven implementation of the Act and highlights the need for targeted interventions to ensure equitable recognition of forest rights across all regions.

| States | No. of Titles Distributed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Up to 31.05.2025 | |||

| Individual | Community | Total | |

| Andhra Pradesh | 2,26,651 | 1,822 | 2,28,473 |

| Assam | 57,325 | 1,477 | 58,802 |

| Bihar | 191 | 0 | 191 |

| Chhattisgarh | 4,81,432 | 52,636 | 5,34,068 |

| Goa | 856 | 15 | 871 |

| Gujarat | 98,732 | 4,792 | 1,03,524 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 662 | 146 | 808 |

| Jharkhand | 59,866 | 2,104 | 61,970 |

| Karnataka | 14,981 | 1,345 | 16,326 |

| Kerala | 29,422 | 282 | 29,704 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2,66,901 | 27,976 | 2,94,877 |

| Maharashtra | 1,99,667 | 8,668 | 2,08,335 |

| Odisha | 4,62,067 | 8,832 | 4,70,899 |

| Rajasthan | 49,215 | 2,551 | 51,766 |

| Tamil Nadu | 15,442 | 1,066 | 16,508 |

| Telangana | 2,30,735 | 721 | 2,31,456 |

| Tripura | 1,27,931 | 101 | 1,28,032 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 22,537 | 893 | 23,430 |

| Uttarakhand | 184 | 1 | 185 |

| West Bengal | 44,444 | 686 | 45,130 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 429 | 5,591 | 6,020 |

| Total | 23,89,670 | 1,21,705 | 25,11,375 |

(Source: Ministry of Tribal Affairs, 2025 [12])

As of May 31, 2025, the distribution of titles under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, across various states and Union Territories reveals significant disparities in implementation. Chhattisgarh stands out with the highest number of titles distributed, totalling 534,068 across both individual and community categories. This reflects the state's extensive engagement with forest-dwelling populations and its administrative commitment to recognising forest rights. In stark contrast, Uttarakhand has recorded the lowest number of titles distributed under the FRA, with only 185 titles issued. This discrepancy highlights the uneven progress in operationalising the Act and underscores the need for more inclusive and regionally responsive policy interventions.

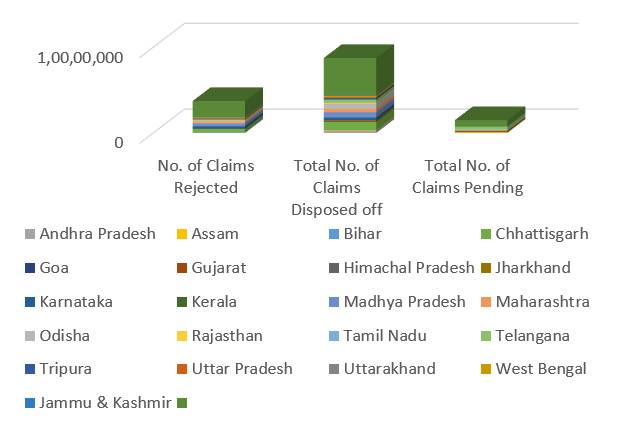

[Fig. 1] illustrates the status of implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) across Indian states and union territories, highlighting the number of claims rejected, disposed of, and pending nationwide as of 31 May 2025.

Chhattisgarh records the highest number of claim rejections, while Odisha reports the lowest. Telangana has the greatest number of pending claims, in contrast to Assam, which has the fewest. Notably, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand have no pending claims, indicating that all

submitted claims have been processed. Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, and Jammu & Kashmir also exhibit minimal pendency.

Himachal Pradesh demonstrates the lowest rejection rate, whereas Kerala reports the highest. Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra are tops in total disposals and rejections, signifying vigorous execution accompanied by thorough monitoring. Telangana and Odisha possess a substantial volume of pending claims, showing administrative obstacles. States such as Kerala and Himachal Pradesh exhibit limited claim activity, either attributable to smaller forest-dwelling populations or stronger past land legalisation. The data indicate inconsistent implementation of the Forest Rights Act throughout India. Although several states have finalised or are close to finalising processing, others still encounter elevated pendency and rejection rates, indicating difficulties related to documentation, understanding, or bureaucratic obstacles experienced by forest-dependent and indigenous populations.

In Kerala, 29,422 recipients received Individual Forest Rights (IFR) covering 38,794.10 acres. The state government has indicated the absence of significant administrative impediments, according to that statement. Whereas in Chhattisgarh, 481,432 individuals got forest rights as of May 2025[12]. Chhattisgarh is home to a significant population of forest-dwelling tribals who have high expectations for the recognition of Community Forest Rights (CFR) and Individual Forest Rights (IFR). However, various independent analyses and news reports from 2024 to 2025 indicate that the recognition process for CFR is progressing slowly and is often challenged, with evidence of departmental resistance and a backlog of pending claims. Nonetheless, the difficulty has been in obtaining recognition for these rights. Chhattisgarh is a central Indian state where widespread CFR acceptance is expected. The region is inhabited by 7.8 million Adivasis, representing 31% of the state's population, with over 90% residing in rural areas. Furthermore, around 66% of the rural population lives below the poverty level. Chhattisgarh is a densely wooded state, with the Recorded Forest Area (RFA) constituting over 45% of its geographical expanse, and nearly 50% of the villages situated within a five-kilometre radius of forest. Consequently, for the residents of these villages, predominantly comprising Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers, woods serve as the principal source of subsistence and sustenance.

Chhattisgarh’s large tribal population and forest size increase administrative burden and enhance the appeal of those lands for mining and industry; Kerala's tribal population and forest area are comparatively smaller and more manageable at a local level. Kerala’s recovery rate of forest land is very high compared to other states. 15,768.48 hectares of land remain unrecovered in Tamil Nadu, while 86,348.44 hectares in Karnataka were encroached, and only 11,196.64 were recovered. Implementing the FRA is facilitated in numerous districts; however, forest encroachment, recovery, and human-wildlife conflict remain significant policy challenges. In Chhattisgarh, the presence of Left-Wing Extremism and elevated insecurity in some districts restricts outreach, verification, and the facilitation of Gram Sabhas in such regions. The mining and industrial interests, along with plantation economies in Chhattisgarh, generate conflicts that impede recognition. In Chhattisgarh, initiatives by the forest department and administrative stances have occasionally hindered the implementation of Community Forest Rights (CFR).

ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITY OF THE ACTORS IN IMPLEMENTING THE FRA

Forest Rights Committee (FRC): It receives and formally acknowledges claims submitted in designated formats, accompanied by the requisite evidence to support for each assertion. Compiles a list of applicants through comprehensive verification of claims related to forest rights. The FRC compiles documentation of claims, generates maps, and determines lands covered by claims by identifying established landmarks. The body articulates claims concerning community forest rights for the Gram Sabha and delineates its findings on the character and scope of these claims for evaluation. The committee addresses disputes with other FRCs through the organisation of collaborative meetings. If unresolved, the FRC will escalate the claims to the Sub-divisional Level Committee (SLC).

Gram Sabha: It aids in the creation of the FRC and supervises its operational duties. Authenticates all assertions, documentation, and maps generated by the FRC and evaluates them before submission to the SLC.

Sub-Divisional Level Committee (SDLC): This body, formed at the sub-divisional level, assesses the resolutions enacted by the Gram Sabha, consolidates the documentation of forest rights, and presents it to the DLC for final judgment.

District Level Committee (DLC): The District Collector chairs the committee and eventually accepts the forest rights record generated by the SLC. The DLC's decision regarding the forest rights record shall be conclusive and obligatory. The procedure entails the acknowledgement and assessment of grievances from those dissatisfied with the SLC's determination.

State Level Monitoring Committee: Established at the state level, it comprises officials from the tax, forest, and tribal affairs ministries of the state government, responsible for the acknowledgement and distribution of forest rights[8].

THE FRA PROCESS AND DECENTRALISATION

The FRA process commences with the crucial step of establishing the Forest Rights Committee (FRC) through elections conducted by the neighbouring community or Oorukoottam, which may comprise individuals from the same or different tribal groups. The FRC is therefore established at a level subordinate to that specified in the Act, specifically the level of the Grama Sabha. The FRC enables tribes to submit claims for titles. A collaborative survey is thereafter executed by the Panchayat Forest Department and the Revenue Department, culminating in the finalisation of claims. These are thereafter forwarded to the SDLC. and thereafter to the DLC for ratification and issuing of Records of Rights. Petitions challenging the FRC's judgment may be submitted to the SDLC, while those contesting the SDLC's decision may be directed to the DLC. The DLC holds ultimate jurisdiction over the Record of Rights. The Forest Rights Act facilitates decentralised local governance by empowering forest-dwelling communities, particularly tribal groups, to participate in decision-making processes concerning forest management. It establishes a democratic framework for recognising and addressing instances where community rights may be infringed upon by conservation initiatives. When a tribal community holds legally recognised rights over forest land, it also possesses the authority to be consulted on any proposed changes to the forest and to oppose actions that threaten its ecological integrity or their customary use.

The states and Union Territories' monthly progress report of the FRA has been submitted to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs. According to State/UT reports, as of May 31, 2025, 51,23,104 claims—49,11,495 individual and 2,11,609 community claims—had been submitted at the Gram Sabha level. This included 23,89,670 individual and 1,21,705 community titles, for a total distribution of 25,11,375 (49.02%) titles. In all, 7,49,673 (14.63%) claims have been waiting for disposal, while 18,62,056 (36.35%) claims have been denied. A total of 29,422 beneficiaries have been granted individual forest rights to 38,794.10 acres of land by the State Government of Kerala[12]. The Government of Kerala's proposal to establish Forest Rights Act (FRA) cells at both the state and district levels has received approval from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, accompanied by a financial allocation of ₹129.89 lakhs. Furthermore, the state government has directed District Collectors to reclassify Scheduled Tribe-inhabited areas as revenue villages, following the conferment of individual forest rights under the provisions of the Forest Rights Act. In cooperation with other state departments or on their own, livelihood programs are being carried out through the Central Government's PM-JANMAN and Dharti Aaba Janjatiya Gram Utkarsh Abhiyan (DA-JGUA) schemes, as well as other State Government programs[12].

Members of a Scheduled Tribe or other Traditional Forest Dwellers possess the legal entitlement to make a livelihood through the cultivation of their land. This provision addresses the longstanding marginalisation of forest-dwelling communities—particularly Scheduled Tribes—whose access to land and resources has historically been restricted due to the enduring legacy of colonial forestry policies. For ages, Scheduled Tribes have inhabited forest regions without formal titles; nonetheless, the government granted legal rights to forest land during the British period. In the pre-colonial era, local populations managed forest resources, deriving their livelihoods from these regions with limited governmental intervention[15]. The Indian Forest Act of 1865 established forest policy of British India, transferring significant portions of forest land to government possession and invalidating the ancestral rights of millions of forest inhabitants. After independence, the government's regulation of forests continued without addressing the rights of forest communities. The absence of formal titles and increasing industrial demands resulted in the re-use of forest areas and the displacement of millions of forest inhabitants. This has often resulted in contradictory claims on forest land ownership between the government and forest inhabitants. The FRA guarantees land security for forest communities displaced from their native territories due to colonial resource extraction, modern free-market economic development, and efforts to conserve the environment.

The Act's primary goals were to restore the tribals ' customary rights, stop the historical injustice they had experienced over land dispossession, and "contribute to a more structured conservation approach."[23]. The FRA specifically intended to provide Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers with legal acknowledgement and tenure of forestlands they have inhabited for numerous generations. Nonetheless, this has never been historically recorded concerning the "historical injustices arising from the consolidation of State forests during the colonial era and in independent India." The FRA was formed to address the persistent instability of possession and access rights for Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest inhabitants, especially those who were displaced by state development projects. The Act provides a framework for documenting these rights and specifies the forms of evidence required to recognise and confer these individual rights in forestland[17].

Contrary to common opinion, it is neither a land acquisition nor a land allocation, nor does it entail the provision of new forest land. The Act aims to enhance forest conservation efforts and ensure the livelihood and food security of Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest inhabitants by delineating "the responsibilities and authority for sustainable utilisation, biodiversity conservation, and ecological balance maintenance." This is crucial for protecting the necessities of forest dwellers and enhancing local governance of forests and other natural resources. It ensures the sustainable utilisation of resources in these regions and the community's preservation of forests. The FRA grants Gram Sabhas, or village councils, the legal authority to manage, safeguard, and govern the forests associated with their community forest rights. The Act encompasses a comprehensive spectrum of entitlements, including individual rights related to self-cultivation and habitation, as well as collective rights concerning grazing, fishing, and access to forest water bodies. It further extends specific provisions to Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), ensures access to biodiversity, and acknowledges ancestral seasonal resource utilization by pastoral and nomadic communities. The Act also affirms the recognition of traditional customary practices and confers the right to protect, regenerate, conserve, and sustainably manage community forest resources. Additionally, the FRA authorizes the allocation of forest land for community development purposes, thereby facilitating the establishment of essential infrastructure within forest-dependent settlement. The FRA, in conjunction with the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Settlement Act of 2013, safeguards tribal inhabitants from eviction without rehabilitation and settlement[6].

Additionally, they possess the power to authorise or reject any governmental conversion of these forestlands for other uses, including various development initiatives (such as mining, industrial projects, or dam construction). Before the enactment of the FRA, only political leaders and forestry officials possessed the right to determine such diversions. Globally, including within India, there exists a substantial body of evidence demonstrating the efficacy and value of community-based forest governance and inclusive conservation strategies. These approaches have consistently contributed to enhanced ecological outcomes and improved socio-economic conditions among forest-dependent communities. On February 13, 2019, the Supreme Court mandated that state governments ensure the eviction of about 1.1 million tribals from forest regions across 17 states by July 27, with the order being made public on February 20. On February 28, the Supreme Court delayed the ruling in response to a request by the Union Government to change it, allowing states to halt the expulsion of tribal members temporarily[17].

FRA’S IMPACT ON FOREST CONSERVATION AND TRIBAL LIVELIHOODS

By legally acknowledging the rights of the Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers to use, manage, and protest forest resources, the FRA impact on forest conservation and tribal livelihoods. The FRA is intended to empower forest communities and advance sustainable forest development. The fundamental element of the Act is to empower Gram Sabhas, a democratic institution at the village level. The FRA promotes decentralised and participatory governance by giving these bodies authority. The Supreme Court enforced the eviction of individuals who claimed rights under the FRA were rejected on February 13, 2019. An estimated 1.8 million individuals could be impacted by the widespread protests that followed[19]. Hundreds of thousands of forest inhabitants now live in extreme insecurity because of the Court's 2019 ruling and the ensuing implementation delay, which has also undermined grassroots conservation initiatives. Progress has been disrupted specifically by the tardiness in acknowledging Community Forest Resource (CFR) rights.

The traditional practices of the tribal communities have been acknowledged by law under the FRA. Maintaining traditional conservation methods that have been essential to India's ecological legacy depends on this recognition. Communities are encouraged to manage forests appropriately when they have secure tenure, which improves biodiversity and climate resilience. Long before the FRA took effect, in 1977, the people of Teen Mouzas, in the Nayagarh district, Odisha, established a Forest Protection Committee. After receiving legal recognition under the FRA, their unofficial conservation activities developed into official processes, and in 2021, they formed a Community Forest Resource Management Committee (CFRMC) under Sections 3(1) and 5 of the Act. Another example of community conservation is in Soura Kurlanda in the Gajapati district, a Reserve Forest area that was formerly hampered by wood smuggling. Tree-cutting was strictly prohibited by the Lanjia Soura group, which is categorised as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group. They strengthened their conservation efforts in February 2025 by securing 84.5 hectares under CR and CFR rights[19]. Such recognition has ecological benefits. Communities are encouraged to manage forests responsibly when they have secure tenure, which improves biodiversity and climate resilience.

CHALLENGES IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FRA

Tribes and other traditional forest-dwelling populations face numerous, complex challenges in securing their forest rights and means of subsistence. The FRA stipulates that the conversion of forest land requires approval from the Gram Sabhas and must take place after the implementation of the FRA. Between 2008 and 2016, approximately 3.1 million hectares of forest land were diverted for non-forest uses without the approval of the Gram Sabhas. Frequently, a positive District Administration report was enough to support forest diversion for development initiatives[3]. Before FRA’s introduction, the Forest Department had already moved several forest communities in numerous protected areas. According to the FRA, communities should have the option to maintain their rights and obligations while residing in a protected area, with any necessary modifications to these rights agreed upon by both parties[14]. According to FRA regulations, the Forest Departments play a minor role in the execution of the FRA. But they are regarded as exercising a veto power by denying people their rights and dismissing their arguments during the screening process[13].

Administrative apathy is one of the major challenges in implementing the FRA. The existing law and already claimed illegal encroachments can be rejected easily; also, the Act is not easily amenable, and inconsistent implementation results from many states' failure to schedule regular meetings of the FRA bodies. There have been instances of state governments' unwillingness to implement the FRA in its entirety, as seen in the example of Himachal Pradesh, which has the worst record of FRA compliance while having one of the largest percentages of the total land area classified as forestland[7]. Similarly, governments are not inclined to emphasize the appropriate execution of the FRA due to issues such as the glaring lack of administrative empathy and concern caused by the small vote bank percentage of indigenous populations in the Scheduled areas[22].

The forest administration is often reluctant to acknowledge the rights of communal forest resources[4]. Thus far, community forest rights have been neglected in favor of individual forest rights, which are assertable under the FRA. The resistance from the forest officials comes in several forms. The tribal people's decreased reliance on their officials is the root cause of the dissatisfaction at the lowest level. There are significant ideological divides between local communities and the Forest Department. The Forest Department still has doubts about the Gram Sabhas' competence to manage and conserve woods, notwithstanding the law's transfer of rights to the communities. They might be in favor of pre-FRA procedures that give them more authority, such as Joint Forest Management (JFM) committees[1]. The requirements of the FRA (and particularly the CFR) are not well known in many indigenous communities or grama sabhas. As a result, they have not worked hard enough to submit their claims. They have not received sufficient encouragement from government agencies to pursue this direction. Because development projects are started without the gram sabha's proper authorisation, traditional forest dwellers are always in danger of losing their lands, means of subsistence, and forests[2].

In addition, there are numerous examples, such as in Kerala, where organised opposition from non-Adivasi workers and settled farmers caused the government's efforts to be delayed. In addition, even in cases where the residents of small tribal communities were given nominal possession rights, the FRA has utterly failed to provide them with actual access to and ownership rights over land and forests[9].

The evaluation of the FRA's impact reveals multiple variables leading to its insufficient execution. This includes a lack of political commitment at both state and national tiers, inadequate initiatives to strengthen ability at the national level, and the creation of contradictory frameworks, like collaborative forest management plans, which authorise the forest department to oversee forest management. The study revealed that the diversion of community forest resources for development projects occurred without the consent of the Gram Sabhas[24].

Notwithstanding its pioneering nature, the Act is deficient in a simplified implementation mechanism. Since its enactment, it has diverged from other policies, including the Van (Sanrakshan Evam Samvardhan) Adhiniyam, 1980 (formerly the “Forest Conservation Act”) and the Wild Life Protection Act, 1972 (“WPA”), which authorise the transformation of forested areas for non-forestry purposes and the establishment of Protected Areas, including tiger reserves. This has simultaneously resulted in a dispute involving the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC), the judiciary, civil society, and the bureaucracy. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) is the primary ministry for the Forest Rights Act (FRA); however, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) serve as the principal agency within the administrative structure for implementing India's environmental and forestry policies, leading to ongoing conflicts between the two regarding the FRA. The highlighted problems are primarily ascribed to institutional deficiencies, incompetence by authorities, legislative discrepancies, and inaccurate data records[1]. Contradictory opinions on law and gatekeeping (who holds the ultimate authority) between the MoEFCC and Mota is one of the major obtacle in implementing the FRA.

The Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) is the designated authority for the Forest Rights Act (FRA); nevertheless, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and forest departments frequently interpret FRA results in accordance with forest conservation laws, thereby exerting supervisory authority. This results in state officials either awaiting MoEFCC approval or reinterpreting FRA regulations in a manner that constricts rights. This causes a delay and may negate or weaken the conclusions of the Gram Sabha (Aggarwal). State-level offices and District Level Committees occasionally encounter contradictory directives from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (or from their respective state-level equivalents and the forestry department). When the MoEFCC or Forest Department mandates supplementary technical surveys (such as satellite assessments and compartment-specific area limitations) or the implementation of conservation rules (e.g., National Working Plan Code), the verification of claims is delayed, or claims are partially approved or reduced. Independent fact-finder’s highlight the habitual practice of forest departments admitting only portions of Gram Sabha Community Forest Resource claims. The relationship between FRA rights and clearances for public infrastructure projects, which generally necessitate MoEFCC clearance under the FCA, is ambiguous. Occasionally, project approvers perceive FRA rights as an additional obstacle rather than a rightful entitlement, or alternatively, regard FRA as inadequate to avoid delays—resulting in contradictory outcomes and legal ambiguity that hinders recognition or renders rights contingent.

The observation reveals that the Gram Sabhas, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers demonstrate a considerable deficiency in awareness concerning the legislation and their entitlements. The FRC members' misinterpretations, along with cunning bureaucratic interference, have obstructed the communities' understanding of the procedures and the law. Although several governments, like Chhattisgarh, have optimised legislative frameworks using awareness initiatives and guidelines, it is predominantly civil society that have become crucial actors in these campaigns. Due to a lack of awareness, community rights titles often stay unclaimed despite an absence of significant time. The reasons cited for this predicament encompass the absence of committee members and inadequate quorum, among other issues, indicating a calculated delay in the procedure. Consequently, there are instances where titles (patta) are awarded provisionally, referencing these justifications[20].

IMPACT ON TRIBAL LIVELIHOODS

The FRA gives tribal and forest-dwelling groups more economic stability, food security, and independence from middlemen by safeguarding their rights as well as their access to land and forest resources. Development initiatives that are started without the Gram Sabhas' proper consent have put indigenous tribes in constant danger of losing their lands, means of livelihood, and forests. To obtain land for development projects, the state has used its eminent domain power without taking into account various laws, including the Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act of 1996, the Forest Rights Act of 2006, and the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act of 2013[2].

The inefficiency of authorities has hindered the implementation of the Forest Rights Act, resulting in a lack of awareness among indigenous people about numerous parts of the law. The ambiguity created by the indigenous tribes' ignorance could result in a misunderstanding of their rights. The denial of their legitimate rights is a major obstacle that tribes must overcome. Because they are frequently exploited by authorities who take advantage of their ignorance, tribes frequently struggle to establish their land rights. There is little involvement of tribal people in forest management decision-making processes that directly affect them. By giving them land rights expressly for agricultural purposes, the FRA of 2006 aims to strengthen the economic standing of indigenous people.

The indigenous populations, once closely linked to forested areas are currently facing challenges that have made their daily lives difficult. The imposition of limitations on forest resource exploitation, agricultural activities, and shifting cultivation practices has led to significant disruptions in traditional lifestyles. The inability to collect tubers, animal flesh, honey, and other fruits, along with restrictions on the cultivation of traditional crops such as ragi, corn, tiny millet, and sorghum, has forced them to leave their forest habitats. The necessity of securing food through agricultural labor and external employment has led to the adoption of various dietary practices, which include detrimental habits such as alcohol consumption and tobacco use, resulting from heightened interaction with mainstream society. This has raised an existential dilemma among the indigenous population[5].

Modern livelihood options are becoming increasingly common, but indigenous groups still lack access to supportive programs. People's lives have changed significantly because of the FRA's enforcement, which limits the use of forest land and decreases the supply of residential real estate. According to a displaced resident who detailed the shift, they used to depend on the forest for supplies and food, but now they work for pay, use their income to purchase products from the neighbourhood market, and are living in worse poverty. A significant constraint identified is the difficulty in gathering forest resources for sustenance. Tribal populations face additional challenges due to restrictions placed by forest authorities on activities including the collection of firewood with knives, bamboo harvesting, willow trimming, and fishing within forest boundaries. The challenges are exacerbated by the demanding process of daily collection of tubers and other essential items[5].

A study of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, and its implications for the livelihoods of Tribal communities in Wayanad District, Kerala, India, authored by Merlin Mathew and K.B. Umesh observed that, notwithstanding Wayanad's status as a progressive district in Kerala with respect to the enforcement of the Forest Rights Act, only 55.12 percent of the Individual Land Rights claims are being granted. The unrecognised capabilities of ILR holders persist in obscurity. The absence of fervour from the pertinent departments obstructs the implementation of community rights allocation within the district. The execution overlooked the daily variations and social inequalities present within the local communities[10]. Only one of the four primary tribal groupings exerted a substantial impact on their socioeconomic conditions. While rectifying the historical injustice was the primary objective, this technique did not achieve it entirely. The socioeconomically disadvantaged class from that era continues to experience an unchanged standard of existence. The fundamental aim of the FRA should be the improvement of indigenous groups' livelihoods and land development. The increasing human-animal conflict has emerged as a significant concern for many indigenous people, since they continue to regard their forest land as integral to their identity[10].

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION

To ensure the effective implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), it is imperative to introduce targeted recommendations at both the policy and administrative levels. Some of the recommendations at the policy and administrative levels are given below;

a. Policy Level Reforms

Clarify the institutional roles and responsibilities of MoTA and MoEFCC to formulate a collaborative operational framework designating MoTA as the principal authority for FRA implementation, with MoEFCC's responsibilities confined to ecological guidance and coordination and incorporate FRA into national and state forestry policies.

Ensure the legal protection of Gram Sabha resolutions and render Gram Sabha resolutions obligatory, subject solely to judicial scrutiny.

b. Administrative level Reforms

Establish specialised units for FRA implementation: Establish FRA Cells at the district and sub-district levels, staffed by trained personnel from the revenue, tribal, and forest departments, under the direct oversight of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA).

Guarantee that all denied claims are examined with documented justifications and provide appeals at every tier (SDLC → DLC → State-level FRA Committee).

c. Livelihood Integration

Integrate the execution of the Forest Rights Act with MGNREGA, PM Van Dhan Yojana, and other initiatives for forest restoration and as a source of livelihood.

d. Enhancement of Capacity and Awareness

Develop the capabilities of Gram Sabha

Facilitate community training on FRA protocols, mapping, documentation, and sustainable forest maintenance.

Facilitate collaborative capacity-building initiatives for officials from revenue, forest, and tribal departments to assimilate FRA principles.

CONCLUSION

Enacted in 2006, the Forest Rights Act (FRA) constitutes a pivotal milestone in the legal framework of post-independence India. This Act is essential for the rights of millions of tribal and forest-dwelling inhabitants across the nation, since it facilitates the restoration of previously lost forest rights throughout India, encompassing individual rights to cultivated land inside forest areas and community rights over shared resources. The Act strengthens psychological security and promotes long-term land investment for persons who successfully obtain their rights. A significant issue is the inadequate implementation, resulting in a high frequency of claim denials, which hinders benefits for many categories. Certain communities have experienced improved socio-economic conditions, while others have faced adverse consequences due to difficulties in claiming and implementing their rights. These difficulties appear in many ways, depending on the various states in India. Kerala serves as an example of comparatively easier implementation, thanks to proactive administrative efforts, smaller tribal populations, and stronger local administration systems. Chhattisgarh and other mineral-rich, forest-dominated states, on the other hand, show slower and more contentious implementation because of the dominance of the forest department, insecurity in areas afflicted by Left-Wing Extremism, and conflicting land-use interests. These regional differences demonstrate how local political will, civil society involvement, and socioeconomic circumstances significantly influence FRA outcomes. Administrative disagreements, opposing agendas between the MoEFCC and MoTA, a lack of departmental cooperation, and lack of knowledge among the beneficiaries are the main causes of implementation difficulties. Confidence in the process has been further undermined by the lack of standardised procedures for claim verification, ambiguous land records, and the frequent denial of claims without sufficient explanation. The basic structure of the FRA process, Forest Rights Committees (FRCs), frequently lack sufficient autonomy, technical assistance, and training at the local level. These committees operate under the influence of revenue or forest officials in many states, which undermines the Act's goal of Gram Sabha-led decision-making.

To ensure the successful implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), it is essential to undertake comprehensive and targeted measures at both the policy and administrative levels. This entails reassessing current legislative frameworks to remove ambiguities, enhancing institutional accountability, and assuring conformity with the principles of social justice and rights for tribal communities. There is a necessity for capacity-building efforts, optimised claim verification processes, and improved coordination among forest agencies, local governance bodies, and civil society organisations. Moreover, incorporating community involvement and open oversight procedures can greatly enhance the legitimacy and effectiveness of FRA execution. Collectively, these methods can reconcile legislative provisions with actual conditions, thereby empowering forest-dwelling communities and fostering sustainable forest governance.